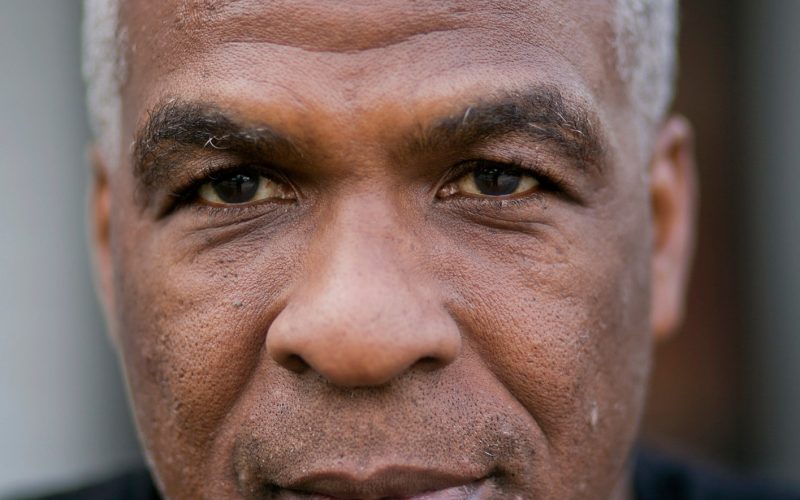

CLEVELAND — Charles Oakley pushed his hands into his pockets and peered at the small photo of himself on the street sign that bore his name. The younger version of himself in the photo was vintage Oakley: the high-top fade, the furrowed brow, the familiar blue and orange of his Knicks jersey.

“Not bad, huh?” Oakley said on an overcast afternoon last week.

A longtime enforcer on a Knicks team that leaned on his ferocious rebounding and lunch-pail attitude through much of the 1990s, Oakley is also a proud son of Cleveland, which honored him recently by feting him with the street sign — Charles Oakley Way — in front of John Hay High School, his alma mater.

When Oakley returned last week it seemed fitting that, just down the block, workers in hard hats were doing construction. Oakley, who still cuts an imposing figure at 52, did not see the symbolism. All he saw was the big mess on his new street.

“They making me look bad!” he said, deadpan.

It was a good time for Oakley to be back in Cleveland. He had tickets that night to see the Cavaliers, who were just months removed from their run to an N.B.A. championship, open their season against the Knicks at Quicken Loans Arena. And the Indians were back in the World Series for the first time in 19 years and looking for their first title since 1948. The success of both teams had the city buzzing, and Oakley was glad to be around it.

“I’ve been through a lot here,” Oakley said. “I’ve seen a lot.”

Oakley splits his time among Cleveland, Atlanta and New York, where he has a studio apartment outside the city. But his 81-year-old mother, Corine, still lives in Cleveland, and he considers the city home. He remembers when downtown bustled.

“The city used to have four legs,” Oakley said. “Now it’s got two and a half.”

As he maneuvered his S.U.V. along Superior Avenue and approached his childhood home on East 123rd Street, Oakley pointed to some of the spots that he frequented as a boy, places that have been replaced or boarded up. The record store. The barbecue joint. The corner market. The barber shop. Back then, he said, the neighborhood was tightknit.

“Everybody looked out for one another,” he said.

Oakley had to catch two buses to his old high school, where he was a star in football and basketball. He also became known for his work ethic, habits that he had picked up from spending time with his grandfather, a farmer in Alabama. Oakley was never known as a leaper. But he worked hard, and rebounding was work, plain and simple.

More on NY Times

Leave a Reply